Platform ad archives in Article 30 DSA

by Paddy Leerssen, Institute for Information Law (IViR)

Disclaimer: Dear reader, please note that this commentary was published before the DSA was finalised and is therefore based on anoutdated version of the DSA draft proposal. The DSA’s final text, which can be here, differs in numerous ways including a revised numbering for many of its articles.

Tucked away in the depths of the new DSA draft, Article 30 carries a title only an academic could love: ‘Additional online advertising transparency’. Please bear with me, because I want to argue that it represents a significant shift in the governance of online advertising. I’ll first explain what Article 30 does, why it matters, and then zoom in on some of the details of this ambitious but flawed proposal.

What Article 30 does

Article 30 DSA regulates platform ad archives. It requires platforms above a certain size (the so-called ‘Very Large Online Platforms’) to publish a registry detailing the advertisements sold on their service, along with certain metadata: the identity of the ad buyer, the period the ad was displayed, audience demographics, and information about how the ad was targeted. The result: ads which were previously only visible to their target audience, become a matter of public record.

Here the DSA is building on earlier precedents in co- and self-regulation. Comparable ad archive rules have already been proposed and even enacted in several jurisdictions, including Canada and the State of Washington. The European Commission’s co-regulatory Code of Practice on Disinformation also contained ad archive rules. Platforms including Facebook and Google have responded with their own self-regulatory measures, although these have been criticized widely for their limited scope, inaccurate data and spotty implementation. The DSA would create a binding regime in an attempt to expand and improve on these self-regulatory outcomes.

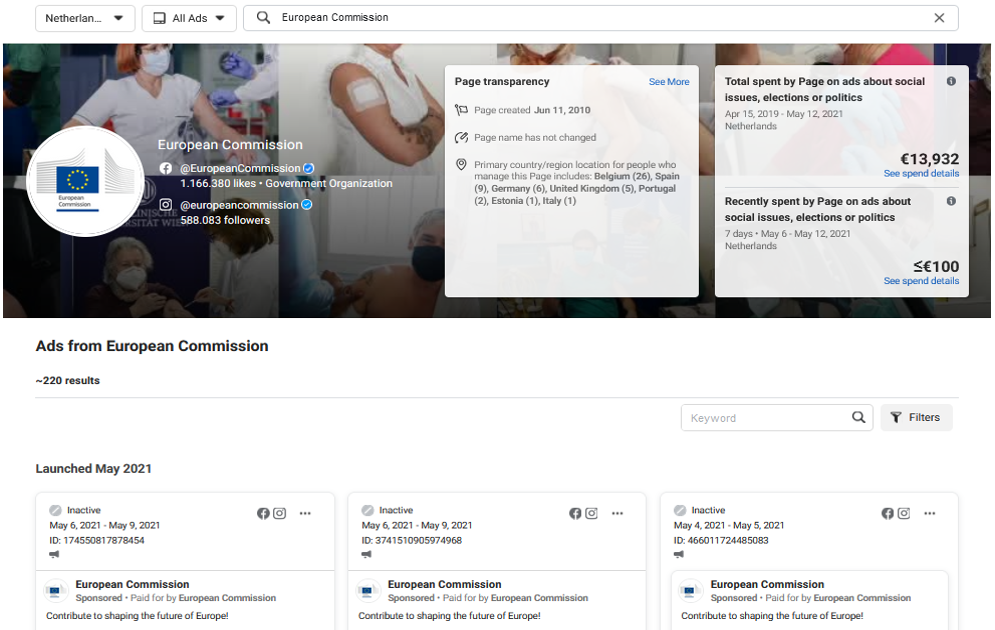

The Facebook Library – to be regulated under Article 30 DSA (Source: Facebook)

Why Article 30 matters

Ad archives represent a significant change in the way online advertising works. Previously, most personalised advertising was only visible to the specific individuals it targeted. These microtargeted ‘dark ad’ methods were seen to foster impunity, since governments and watchdogs could no longer see what messages were being spread. In politics, microtargeting has been accused of undermining electoral accountability, by allowing candidates to signal different campaign promises and policy priorities to different constituents. This “fragmentation of the public sphere”, as my colleague Tom Dobber terms it, also undermines the capacity for third parties to engage in argument, address falsehoods, and sanction unethical or unlawful behavior. Creating a public record, in theory, shines a proverbial light on these dark ads.

Of course, transparency is only a precondition for public accountability, not a guarantee. Will any of this data actually be used? Much depends on this question. Early evidence suggests, however, that even the incomplete and unreliable ad archives provided by platforms on a voluntary basis are starting to have an impact. The archive is cited in a growing number of academic papers, and even as evidence in legal proceedings. In my own empirical research (forthcoming soon), I explore how journalists have started to make use of the Facebook Ad Library for a variety of purposes, including campaign reporting, fact-checking, monitoring hate speech, and calling attention to corporate and foreign state influence campaigns. All this leaves me confident that ad archive data is finding an audience. If data access is regulated to become more accurate and dependable, as the DSA now proposes, we can only expect uptake to increase further.

The attention for ad archives responds primarily to concerns around online political microtargeting (PMT), and its influence on our democracies. These originate from the 2016 Brexit Referendum and US elections, and have since been raised in European countries as well. At the same time, we shouldn’t overstate the urgency of microtargeting concerns in the EU. PMT is relatively uncommon in most European countries, certainly compared to hotspots such as the US and the UK where by far the most money is spent and the most controversies have occurred. Still, the trend is towards increased PMT, so Article 30 can at a minimum be seen as a wise precaution.

The possible applications of ad archives are various. As a public resource, anyone can theoretically use them. Broadly speaking, however, a key function may be to facilitate the enforcement of advertising regulations by regulators and watchdogs, who would otherwise find it difficult or impossible to monitor online advertising activity. Platforms, for their part, often fail to proactively monitor their ads for compliance with applicable laws and conditions. Even if online political advertising is banned outright – as Facebook did periodically last year, as many countries do for broadcast political advertising, and as France does for all advertising in the runup to elections — ad archives can still be instrumental in enforcing such rules. Besides law enforcement, we might also postulate certain ‘softer’ forms of accountability enabled by ad archives. For instance, archives help the aforementioned academics, journalists and civil society actors to study and critique what is being advertised online. For all these reasons, it seems reasonable to expect that advertisers will (be forced to) behave more lawfully and ethically if their advertising is done on the record, especially if this transparency is complemented by robust conduct regulations.

It is worth noting that the EU is simultaneously developing a new framework for the regulation of political advertising under the European Democracy Action Plan (EDAP). The tool developed under Article 30 DSA could therefore play an important role in helping to enforce whatever rules for online political advertising result from this framework.

Notably, Article 30 DSA surpasses its predecessors by extending its scope to all ads, including strictly commercial ads, instead of just political ads that involve elections or social issues. These commercial ads are barely documented in most self-regulatory ad archives, or not at all. Public access to commercial ads may likewise catalyze new monitoring and enforcement strategies, from groups such as consumer watchdogs and regulators. Already, problematic commercial advertising has been discovered and taken down with the help of the minimal data offered by Facebook’s self-regulatory archive.

We must also contend with the commercial applications of ad archive data. Experience teaches us that commercial actors are often the most active users of public transparency resources. Anecdotally, we know that Facebook’s Ad Library is already used by savvy consumers to search for discount codes and by marketers to monitor their competitors’ strategies. Though this may not be the intended purpose of Article 30 DSA, none of this commercial usage appears to be problematic prima facie. After all, this level of transparency is not radically different from the baseline of publicity in mass media advertising. Indeed one might argue that the reduction in information asymmetries between online advertisers facilitates more effective competition.

In the weeds: what article 30 gets right, and what it gets wrong

Comprehensive scope: From political ads to all ads

The DSA may not be the first proposal to regulate ad archives, but it is by far the most ambitious. The biggest change is that, as mentioned, Article 30 would apply to *all* ads sold by very large platforms, and not merely to political advertising. A smart move, since platforms have proven unreliable in detecting political advertising at scale; independent research (example, overview) has shown that their archives have contained countless false positives and false negatives (i.e. failing to include political ads while wrongly including non-political ads). A comprehensive ad archive would allow researchers to define and operationalize their own interest categories, political or otherwise, instead of depending on non-replicable samplings offered to them by platforms. Of course, this also means that commercial advertising can start to be studied and held accountable in new ways.

Targeting data

Another important change is that Article 30 DSA would require platforms to disclose their targeting methods. In self-regulation, platforms including Facebook have refused to publicize targeting methods and instead limited themselves to audience demographics (i.e. “reach” data). Now Article 30 DSA would require them to disclose “whether the advertisement was intended to be displayed specifically to one or more particular groups of recipients of the service and if so, the main parameters used for that purpose”.

Researchers have long demanded access to targeting data, and are likely to welcome this change. But it’s not entirely clear what they’ll receive. The current draft leaves a lot of wiggle room by limiting disclosure to the “main parameters” of targeting (emphasis mine), and it remains to be seen at which level of detail the lawns are drawn in practice. The phrasing has met with criticism from parties including the EDPS, BEUC and Amnesty International, who call for more muscular approaches such as disclosing all parameters, or disclosing the criteria for exclusion (if not inclusion) selected by an ad buyer.

Data protection concerns also constrains what is possible here, since many targeting methods involve personal data, which, pursuant to Article 30(1)’s final sentence must not be included in the archive. For instance, Facebook’s custom audience function targets ads based on lists of telephone numbers, email addresses or other personal data supplied by the advertiser.

Another objection raised by Facebook is that disclosing targeting methods could help to infer information about audience members that engage with an advertisement in the form of likes, shares or comments; since these users were exposed to the ad, one might conclude that they therefore are a member to (one of the) targeted categories. One might ask the question: Is the problem here with the DSA’s ad archive rules, or with Facebook’s public engagement features for advertising? In any case, this example shows how complex the tradeoffs here may be, and indeed how the considerations may differ between platforms.

The devil is, as always, in the details. How, exactly, platform targeting methods can be described meaningfully without publishing the personal data will likely require further standard setting, as afforded by the Code of Conduct for Online Advertising outlined in Articles 36 DSA. Still, a more robust baseline could be expected than the rather weak phrasing now proposed.

Not included: spending data

The DSA takes some important steps forward from self-regulation, but it also takes a step back: inexplicably, spending data are not included. This is a remarkable omission, since spending data have been included in all existing ad archives, such as the Facebook Ad Library, and regulatory proposals, such as Canada’s Election Act. Journalists and researchers have also demonstrated an interest in this data; it recurs in much of the journalism I have studied in my own forthcoming research. Whilst the DSA expands ad archives into commercial advertising, there are no compelling reasons to expect spending transparency in this space to be anything but pro-competitive. So what possible reason is there to hide this data from the public? It’s a striking double standard without a clear policy justification.

Cui bono? Identifying ad buyers

Another pitfall for ad archives is that the listed names of ad buyers can be inaccurate or misleading. In Facebook’s Ad Library, ads were often attributed to unidentified pseudonyms or non-existent organizations. Whether accidentally or intentionally, ad buyers may submit inaccurate information and misstate who’s behind the ad. This problem is less acute for commercial ads, which in most cases aim to advertise an identifiable brand of goods or services. In political and social issue domain, however, advertising is more likely to be funded illicitly, for instance by wealthy individuals, corporations or foreign entities who would rather conceal their involvement.

The present draft requires disclosure of “the person on whose behalf the ad is displayed”. This leaves some ambiguity, since one or more intermediaries, agents or proxies may be involved in an ad purchase. The emphasis on ‘behalf’ arguably demands that a principal rather than an agent must be disclosed, but it is still easy to imagine how intermediaries or proxies could be used to subvert this requirement. Could the language be tightened? Personally I don’t have a definitive fix in mind yet. Perhaps more fleshed out criteria could be considered such as economic control or initiative. Perhaps, on the other hand, this is a matter for subsequent standard setting rather than the text of the DSA.

A related questions is whether the DSA should impose procedural requirements on platforms regarding to verify the identity of ad buyers. Facebook has already ramped up the verification procedures for its Ad Library, and started requiring more extensive documentation from prospective ad buyers, such as a proof of address or personal identification. Should all platforms be held to such a standard? The DSA already contains comparable rules for traders and distance contracts, under Article 22, which demands platforms to obtain contact information from traders and to take ‘reasonable efforts to assess whether the information … is reliable’. (Credit to my colleague Ilaria Buri for pointing out this comparison.)

Veracity requirements could also bind ad buyers in addition to platforms. Such an approach is already visible in Canada’s Election Act, which requires that ad buyers ‘shall provide the owner or operator of the platform with all the information in the person’s or group’s control that the owner or operator needs in order to comply with’ their ad archive rules.

All this being said, my impression is that there are limits to what ad archives can tell us about dark money in online advertising. As I have argued elsewhere, platforms might reasonably be expected to factually verify ad buyers’ identity claims, but it is much more difficult to prevent advertisers from funding proxy agents to buy ads in their own name. Here, advertising transparency intersects with campaign finance regulation, which is a matter for national law. In this regard, ad archives can still provide tangible benefits in offering a *starting point* to investigate and regulate opaque influence campaigns, but – even if rigorously verified — cannot provide all the answers. In this light, it may synergise nicely with the aforementioned European Democracy Action Plan.

Influencers off the hook?

Article 30 is strictly limited to ads sold by the platform, and does not apply in any way to advertising sold directly by content providers (this follows from the definition of advertising in Article 2(n) DSA). Influencer marketing and astroturfing are therefore off the hook. This may be Article 30’s most fundamental limitation, given the growing prevalence of influencer marketing. Indeed, the greater scrutiny imposed on conventional ads by Article 30 DSA could very well push advertising money further towards these largely unregulated alternatives, as a form of arbitrage.

This being said, covering influencer marketing in ad archives is not so straightforward. Platforms do not necessarily have immediate control or knowledge of these activities, and detecting them at scale may prove unfeasible. One intermediate solution, already formulated by Benkler, Faris and Roberts, in 2018, would be to place the burden on platform users to disclose any “paid coordinated campaigns” to the platform, so that these can be included in public disclosures.

Dealing with content takedowns

Unaddressed in the current draft is what should be done with content takedowns. If an ad is removed from the platform, one might plausibly want to remove it from the archive as well. Self-regulatory efforts have been criticized for retroactively disappearing advertisements from their datasets, since they had violated laws or Terms of Service. Is this justified? On the one hand, it is obviously problematic to require platforms to publish potentially harmful content, and certainly content that is illegal. On the other hand, retroactive removals undermine the integrity of the data for researchers. Indeed, the ads that are being taken down are probably some of the most interesting to study, since they tell us about the types of rules being broken online and how platforms exercise their role as gatekeepers.

A happy middle ground would be to retain the entry, including the metadata such as ad spend and buyer identity, while removing or shielding the violative content. This would clarify to researchers that platforms have intervened, and who was affected, without exposing the public to actual content at issue. Violations of platform rules which consist in prohibited but not necessarily illegal content would not always need need to be removed from the Ad Library at all, and would ideally simply be ‘shielded’ with a warning message. As Daphne Keller and I have argued, getting content-level insights is invaluable in the study of platform content moderation. None of this is addressed in the DSA, and would have to be clarified either in the article or in additional standard setting.

Retention periods

Another step back compared to self-regulation is that Article 30’s retention periods are remarkably short: only one year. Facebook’s Ad Library, by comparison, retains ads for a total of seven years. And even this is arguably too short.

The downsides of the DSA’s approach are obvious: the short retention period undermines the ability to perform historical research with the Ad Library. Especially research with lower turnover rates such as regulatory inquiries and academic research will therefore struggle to make good use of the tool. Rarely if ever are their efforts able to conclude within the span of a year. Some of the key uses, therefore, are at risk, and for what? Aside from some marginal cost savings on server space, there appears to be nothing to justify this major restriction in the provisions scope and utility.

Nomenclature: “Libraries” or “archives”?

This brings me to a related point: we used to talk about ‘ad archives’, but increasingly the debate has now shifted to ‘ad libraries’. A subtle but important distinction, since ‘archive’ implies an indefinite retention period, whereas ‘library’ obviously does not. ‘Archive’ also connotes a more objective and comprehensive scope, as opposed to the curated selections of libraries. The term ‘archive’ also invites comparison with the tradition of newspaper archives and the strict ethical standards these are held to. Retroactive removal is taboo in archives; libraries change their offerings daily. Overall, then, ‘archive’ seems like a far more appropriate term for what the DSA has in mind, and what researchers need.

So what explains this shift to ‘libraries’? It seems that Facebook is the culprit: they too used to call their tool an ‘Ad Archive’, but later rebranded it as an ‘Ad Library’. Unfortunately, it seems that much of the public has followed their lead. Notably, this change of course at Facebook came only months after criticism came to light that Facebook had failed to include many relevant political ads in their disclosures, and were alleged to have retroactively removed ads. As Jennifer Grygiel and Weston Sager write:

The changing terminology related to the Facebook ad library demonstrates that the ads database is not as exhaustive as the company purported it to be at launch. The term “library” indicates elective selection and curation as opposed to full and complete stable records that one would expect in an “archive.”

It is a testament to Facebook’s framing power that so many people seem to have gone along with their new ‘library’ branding, despite the significant shift in meaning that it implies.

Article 30 keeps things simple by avoiding both terms – neither library nor archive are mentioned, just the cut and dry ‘additional advertising transparency’. But in surrounding debates we will inevitably need shorthands. For the reasons above I will insist on using the term ‘archive’. Allowing Facebook to reframe these tools as ‘libraries’ will be playing right into their hands.

Conclusion: alternative to regulation, or catalyst?

Overall, then, Article 30 is more exciting than its title may suggest. It represents an entirely different approach to transparency than the largely unsuccessful user-facing disclaimers that have bedeviled the e-Privacy Directive, GDPR and so many other attempts at digital regulations. (Recent experiments from my colleagues involving the DSA’s user-facing labels have confirmed once more how difficult it is to inform users effectively in this way.) Rather than pushing so much more reams of legalese towards end users, ad archives rely on collective oversight from experts and public watchdogs. This may not be the end-all solution to advertising regulation, but it is likely to be a helpful catalyst.

Far more ambitious than existing practices in this space, there are still important weak spots to fault here: the curious omission of spending data, weak language on targeting data, unclear rules for the verification of ad buyer identities and the treatment of takedowns, and unacceptably brief retention periods. However, the basics are certainly there to make a promising first pass.

Perhaps the greatest mistake that the EU could make here, is to treat Article 30 as an alternative to other forms of regulation, rather than as a catalyst. Concerningly, Commissioner Breton appeared to do precisely this. When questioned why the Commission declined to issue a ban on behavioral targeting, his answers was that ‘there will be transparency on ads, there will be a repository & access to data for researchers’. One can disagree on the merits of banning behavioral targeting, but using transparency as an excuse not to do so is clearly unsatisfactory. Transparency alone is not enough, as every researcher in the field will tell you, certainly for powerful platforms that are all too often able to shrug off bad publicity and other forms of ‘soft accountability’. In my view, ad archives are best seen as an instrument to facilitate the enforcement of other binding rules. But if the Commission continues to signal a hands-off approach to advertising, this could rob ad archives of much of their power.

* This article was updated on 6 September 2021