The Missing Metrics in DSA Content Moderation Transparency

By Max Davy, Oxford Internet Institute

The Digital Services Act makes platform transparency reporting mandatory and standardised, but the metrics it requires still fall short of what is needed for real accountability. Counts of removals and appeals alone cannot tell us whether content moderation systems are accurate, proportionate, or effective, making the absence of evaluation metrics such as precision and recall increasingly difficult to justify under the DSA’s risk-based logic. While these metrics are unlikely to surface in baseline transparency reports under Articles 15 and 24, the post argues they may yet emerge through heightened scrutiny of the largest online platforms and search engines (VLOPSEs), as regulatory expectations take shape through enforcement, systemic risk reporting, audits, and related obligations.

How much do you like stumbling across porn on Instagram? Me neither – and as we might expect, it violates Meta’s policies. But not all content containing adult nudity and sexual activity is pornographic, nor does it necessarily violate Meta’s Community Standards (think of Meta’s complicated history with censoring nipples).

If we want to assess whether Meta effectively moderates the many millions of posts that may violate its policies in this area, we can start by looking at how much content Meta actions over time, courtesy of their Community Standards Enforcement Report:

Notice the peak in late 2024, when the number of Meta’s enforcement actions (66.6 million) against adult nudity and sexual activity content roughly doubled compared to the previous quarter?

Suppose we wanted to investigate why this happened. It’s possible that users suddenly started posting way more violative content, or that Meta’s content moderation system became more effective at catching it. More concerning would be if Meta’s system had started over-blocking material which didn’t violate its Community Standards (whether because of changes to company policies, changes to its automated systems, or any number of other reasons).

If this were true, and the spike in enforcement actions happened because Meta was systematically classifying more innocent material as violative, we might then expect more users to complain to the platform and appeal enforcement actions.

Thanks to Meta’s transparency report, we can then check whether this was the case by looking at the total number of user appeals:

Based on this chart, it appears the total number of appeals during this period stayed level. But we should also want to know the success rate of those appeals. Conveniently, Meta also provides us with this information:

So, although the total number of appeals stayed level, this chart shows that the number of successful appeals more than doubled. This suggests that, when Meta ramped up its enforcement actions against adult nudity and sexual activity content in late 2024, there was at least some corresponding increase in content being unjustly blocked or actioned against.

It’s tempting to estimate, based on the number of successful appeals, the precision of Meta’s enforcement actions: that is, the percentage of content Meta legitimately (and illegitimately) blocks under its community guidelines. However, not every innocent person whose content is blocked on Facebook appeals the verdict – and the propensity to appeal varies considerably from person to person and group to group. So, while useful, this data doesn’t tell us the whole story.

How precise are Meta’s enforcement actions, really? Meta could at least help resolve the ambiguity by releasing their own direct estimates of the precision of their enforcement actions. But they don’t, and so we cannot. Our investigatory journey – at least the one which relies on Meta’s transparency disclosures – ends.

There are two lessons to be drawn from this. Firstly, when trying to understand an automated system, it is never sufficient to analyse metrics which are straightforward counts of the digital traces it leaves behind. Automated systems, by definition, do not believe that they make mistakes. Evaluative human judgement is needed for any metric aiming to produce evaluative information about a system.

Secondly, our analysis thus far relies on data that Meta provides to us. Such disclosures, once released voluntarily, are now obligatory under the Digital Services Act (DSA). Articles 15 and 24 of the DSA oblige providers of intermediary services and online platforms, respectively, to periodically release transparency reports describing various aspects of their content moderation practices. This is a unique mechanism to force companies to publish metrics regardless of whether it’s good for their reputation.

The focus of this post is the unfortunate fact that the DSA asks for the wrong metrics – and leaves only indirect routes for correcting this mistake.

Evaluation vs operational metrics

It’s useful to draw a distinction between two types of metrics.

Operational metrics are those which describe the operations of a digital platform – the number of posts, blocks, messages, appeals, complaints, and so on. These are important data, but as we saw in the introductory example, raw data (e.g. # of blocks, # of appeals, etc) are insufficient for evaluating the quality of a moderation system. This is where evaluation metrics become necessary.

Evaluation metrics are metrics augmented by human judgements about whether enforcement actions are legitimate in accordance with a ‘ground truth’, i.e. the platform’s own moderation rules and policies. Examples include precision (what % of blocked content was actually violative?), recall (what % of violative content was caught?) and prevalence (what % of the (viewed) content on a platform is violative?).

The insufficiency of operational metrics is roughly analogous to the ‘dark figure’ in crime statistics, which refers to crimes which go unreported and so remain invisible in official crime statistics. Researchers in crime statistics need to use multiple data sources, such as surveys asking people whether they are a victim of crime, to produce additional evaluative information. In contrast, because tech companies have complete observability over activity on their platforms, they are able to sample content or activity and make these evaluative judgements themselves, rather than having to triangulate from multiple unreliable metrics.

We know from trust and safety professionals, including from Google and Facebook, that evaluation metrics are critically important to internal decision-making in tech companies, and this mirrors my experience as a former data scientist in Canva’s Trust and Safety team. Here’s a quote from the Trust and Safety Professional Association’s curriculum: “Metrics like these can be challenging to generate, but act as an important accountability mechanism that incentivizes companies to continuously improve the true effectiveness of their policies and enforcement systems.”

It’s surprising, then, that evaluation metrics rarely appear in companies’ transparency reports.

Historic lack of evaluation metrics in transparency reports

I’m not the first person to point out this problem. In 2019, a group of independent experts released a report commissioned by Meta (then Facebook) evaluating the metrics in its transparency reports. They called on Facebook to publish measures of recall and precision and similar evaluation metrics for both human and automated judgements. One quote is directly relevant to our introductory example: “Rates of reversal on appeal should be made public, but they should not stand in as the sole public metric of accuracy.”

Facebook then published a non-committal response in which it argued that ambiguous moderation cases would complicate evaluative metrics – despite the fact that the company already used such metrics internally. It’s been more than six years since this report was released, and the suggested evaluation metrics still haven’t been published externally.

This is part of a larger pattern in which digital platforms expand and maintain their power by building rich sources of information about themselves without sharing it publicly or with regulators. Although platforms might protest otherwise, their reluctance to engage in voluntary transparency and facilitate outsider scrutiny is consistent with recent reductions in Trust & Safety investments more generally.

We know from leaked internal Meta documents that Meta estimated 10% its advertisement revenue came from scammers. This is a highly consequential evaluation metric, but was never intended for public consumption. If companies were compelled to publish such metrics themselves, they could find it more difficult to muddy the public debate by claiming, as Meta did in this case, that the leaked evidence “present[s] a selective view that distorts Meta’s approach to fraud and scams.”

The DSA was an opportunity to force companies such as Meta to publish such metrics. The concepts measured by evaluation metrics cleanly map onto the fundamental rights that the DSA aims to promote: recall captures the right of consumers to a safe online experience, and precision communicates the extent to which users’ freedom of expression is being curtailed. These metrics also aid in understanding how companies are balancing between these rights.

Yet the DSA does not call for a single evaluation metric – with one exception. Article 15.1(e) requires platforms to publish ‘indicators of accuracy’ of automated moderation. However, this requirement is both limited in its scope of ‘automated systems’ and has many other problems, so that the information provided under this provision thus far are essentially meaningless.

Any Trust & Safety data scientist could tell you that evaluation metrics such as recall and precision should be included for any ‘transparency report’ worth its name. It begs the question: how did the EU choose what metrics to include?

How metrics were chosen for the DSA

If transparency programs are enacted without reference to a goal, they become useless. The design of any transparency report should start by asking the intended purpose of providing the information, use this purpose to determine what information ought to be conveyed, and only then design metrics to address those aims.

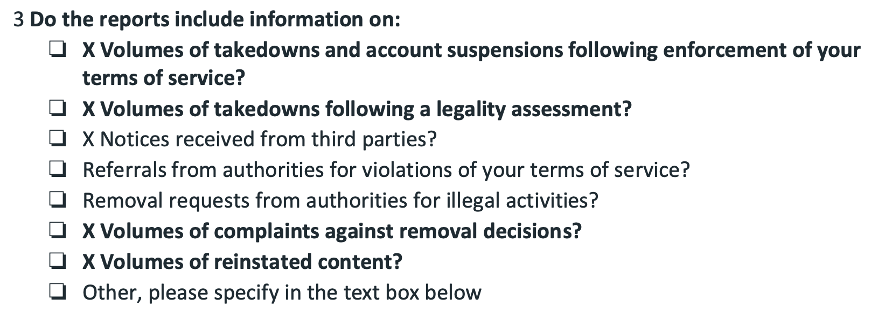

Did the drafters of the DSA follow these best practices? The available evidence from the DSA’s public consultation period (from June to September 2020) suggests they did not. In the Commission’s questionnaire, one question asked companies that already published voluntary transparency reports what metrics were included in those reports:

Screenshot from the Commission’s 2020 consultation questionnaire

This list is very similar to the final set of content moderation metrics stipulated for disclosure under the DSA’s transparency obligations.

Some companies (including, funnily enough, Facebook) did recommend, in their consultation response, alternate methods of choosing metrics. Nevertheless, it appears there was little meaningful change as a result of the consultation (nor of the legislative negotiations that followed), effectively codifiying the voluntary transparency reporting metrics already being performed by Facebook, Google, and other firms in the DSA.

To summarise our analysis: Evaluation metrics clearly align with the DSA’s purpose. However, despite being requested by previous expert panels, despite companies already calculating such metrics for internal use, and despite industry suggestions that the proposed metrics were insufficient, the DSA transparency reporting legislation did not include them.

Can we do anything about it?

Inflexible legislation

One surprising aspect of how the DSA handles transparency reporting is that it specifies a set of metrics, in prescriptive detail, directly in the legislation. Because changing legislation is difficult and slow, this is a nightmare scenario for a data scientist.

It’s commonly understood in industry that metrics need to be quickly iterated upon as edge cases and unexpected subtleties undermine the construct validity of the original definition of metric. This is especially the case for not-yet-well-understood phenomena and systems, such as content moderation systems – see chapter 6 of the data scientist’s bible for measurement for more on this point.

It seems the DSA does not offer a direct path to iterating on its basic transparency reporting requirements under Articles 15 and 24 (unlike some other provisions, there was no delegated legislation provided to further specify substantive requirements; an implementing act was used for prescribing the required format of transparency reporting, but did not touch on metric definitions).

Possible alternative routes for requiring evaluation metrics

For now, it appears that the DSA’s transparency reporting requirements for companies under Articles 15 and 24 are largely limited to disclosing operational metrics. However, other DSA transparency mechanisms might offer a pathway for getting at least the largest online platforms and search engines (VLOPSEs) to publish evaluation metrics.

One option is to push VLOPSE’s to publish evaluation metrics in their annual systemic risk assessment reports, as part of their heightened transparency requirements under Article 42. Both the DSA Civil Society Coordination Group (pages 15-22) and the Integrity Institute (page 35) have called for corporations to accompany their claims about the effectiveness of their content moderation systems with actual proof, including quantitative evaluation metrics. The data access mechanism provided by Article 40 of the DSA, too, provides a complementary route for regulators and independent vetted researchers to potentially scrutinize some of the evaluation metrics that VLOPSEs use internally to measure the efficacy of their content moderation systems.

But we’re not there yet. The initial independent audit reports of VLOPSEs’ risk management obligations and the European Commission’s summary report of prominent and recurring risks on VLOPSEs are first steps toward cataloguing risk management practices, but these documents don’t yet really engage with how the effectiveness of moderation systems should be measured or compared. And although the Article 40 data access mechanism for vetted researchers is now up and running, it will take some time before we know what kinds of insights can be gleaned from such access requests.

Conclusion

This post has argued that metrics included in transparency reports must be developed via a process which carefully considers what evaluative concepts ought to be conveyed, and how such concepts can best be operationalised. I have further argued that such a process wasn’t followed in the design of the Digital Services Act’s transparency reporting framework. The result is a set of metrics that reveal little about the choices, investment, quality, or trade-offs in online platforms’ content moderation systems. Other jurisdictions considering similar legislation, and future reform efforts for the DSA, should consider the simple and impactful addition of evaluation metrics to transparency reporting requirements.

In an ideal world, companies would be compelled to publish high-level evaluation metrics for their content moderation practices in a standardised manner. For now, this gap can be partially closed for the largest platforms via Article 42’s heightened transparency reporting requirements for designated VLOPSEs, particularly with regard to their systemic risk management duties under Articles 34 and 35.

At present, platforms’ systemic risk reports and related audit reports offer some detail about companies’ safety efforts, but rarely include evaluative metrics that would allow outsiders to assess whether those measures actually work. Where companies claim their content moderation measures are effective or proportionate, they should be expected to provide evidence in the form of evaluation metrics to back it up.