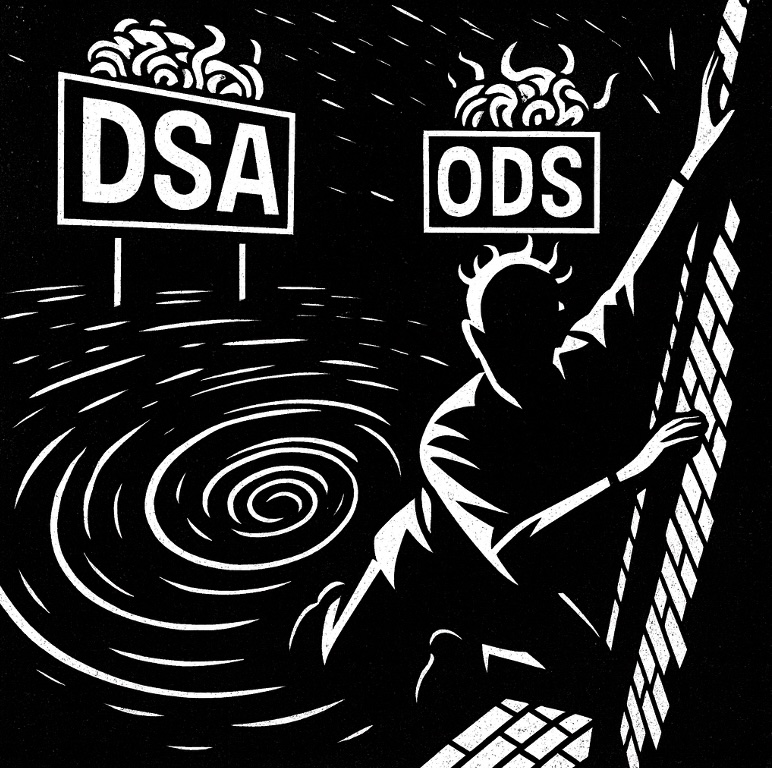

Applicable Law in Out-of-Court Dispute Settlement: Three Vertigos under Article 21 of the DSA

By Lorenzo Gradoni (University of Luxembourg) and Pietro Ortolani (Radboud University Nijmegen)

Article 21 of the DSA entrusts out-of-court dispute settlement bodies with reviewing platforms’ content moderation decisions. But which law should guide them? This post examines three options: terms of service, contract law, and human rights. Each option brings challenges, inducing its own kind of Hitchcockian vertigo. A human-rights-based approach may strike a better balance, reconciling the efficiency of ODS bodies, fairness for users, and the readiness of platforms to cooperate.

Under Article 21 of the Digital Services Act (DSA), certified out-of-court dispute settlement (ODS) bodies are responsible for resolving user-initiated disputes concerning content moderation decisions made by online platform providers, such as the removal or demonetization of content, the suspension or termination of accounts, or the decision to leave content online despite a notice. The potential volume of such disputes is staggering. Since the DSA entered into force, platforms have adopted nearly 35 billion content moderation decisions, each of which could, in principle, give rise to an ODS procedure. Complaints may also be brought in the numerous cases where an individual or entity submitted a notice, but the platform declined to take any moderation measure.

Empirical research indicates that approximately 99.8 per cent of content moderation decisions respond to alleged violations of platforms’ terms of service (ToS), i.e. the contractual arrangement between the platform provider and the user. This raises a question of applicable law: against which normative standards – over and above the ToS, if any – should ODS bodies assess whether a platform’s decision ought to be upheld or overturned?

The question might appear trivial: wouldn’t it be the law that governs any given dispute, i.e., the relevant contractual arrangements and the applicable national law, including relevant supranational and international sources? Two factors make this standard doctrinal answer doubtful in the present context.

First, it is implausible that Article 21 DSA intended to replicate the model of courts – a model notoriously unfit to resolve content moderation disputes at scale. ODS bodies are, in principle, meant to be nimble and cost-efficient, with the non-binding nature of their decisions serving as both the kernel and emblem of that ‘lightness’. Second, Article 21 DSA is a particularly clear illustration of the EU’s predilection for experimentalist governance as a regulatory approach: instead of imposing a single solution to a social problem – such as a rigid legal framework – it establishes conditions under which civil society and the public sector can experiment with a plurality of possible solutions. This spirit of experimentation is already reflected in the emerging ODS ecosystem, now composed of seven operators which appear to adopt divergent approaches to the applicable law (though little is yet known about their actual modus operandi).

As the ODS system is designed to operate at scale, this seemingly technical question carries potentially far-reaching consequences. Determining the applicable law wisely is crucial both for safeguarding the rights of users – including fundamental rights – and for securing platforms’ willingness to accept ODS bodies’ non-binding decisions, without which the system risks collapsing. A recent debate on the role of human rights under Article 21 DSA – fostered by User Rights (a self-reflective ODS body that established its own Academic Advisory Board) – underscores that the issue requires a delicate balancing act rather than reliance on sources doctrine. However, when we first set out to reflect on this theme, we did not expect to feel as off-balance as Scottie Ferguson in Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo.

In the film, Mr. Ferguson, a former detective who suffers from vertigo after witnessing the fatal fall of a colleague during a rooftop chase – a metaphor for an ODS body facing failure – is torn between appearances and reality, estrangement and recognition. Something similar may await ODS bodies under the DSA. In the following, we argue that ODS bodies, when determining the relevant legal framework, face three distinct options: they might confine themselves to the ToS, assessing only whether the platform’s decision complies with its own contractual obligations, without addressing which law governs the contract; they might apply the contract law governing the ToS; or they might ground their reasoning primarily or exclusively in human rights law. A comparative review of the procedural rules of existing ODS bodies shows that they tend to cluster around one of these three approaches. As we shall see, each option seems familiar yet unsettling, promising resolution but courting uncertainty and trouble. In short, each induces its own kind of vertigo. Yet perhaps there is a ledge to cling to: like Scottie, ODS bodies may ultimately overcome vertigo without finding solace, which is precisely what experimental governance’s gritty pragmatism demands.

Option One: Follow the ToS

In Hitchcock’s plot, Scottie Ferguson is deceived into believing he is tailing – and falling in love with – Madeleine, the wife of his old acquaintance Elster. He is in fact observing another woman, Judy, who shares Elster’s plot to kill his wife and disguise the murder as suicide. The stratagem works only because Scottie, paralysed by acrophobia, fails to follow Judy up a bell tower and is then led to believe that she leapt to her death, whereas in fact she was playing her part in the murderous plan. In much the same way, ODS bodies may be drawn to the seemingly attractive option of stopping at – i.e., applying only – the ToS, without realising that, like Scottie halting midway up the bell tower stairs, this move can warp their perception of reality and blind them to its deeper implications.

Appeals Centre Europe (ACE), one of the currently certified ODS bodies, seems to follow this approach in most cases. According to its rules of procedure, eligible complaints are examined by a ‘case reviewer’, who ‘determine[s] if the platform’s decision was made in accordance with the platform’s terms and conditions’. Only if the reviewer is ‘unable’ to make such a determination is the case submitted to an ‘escalation reviewer’ called to apply a broader ‘normative framework’. This framework includes ‘the platform’s stated values, principles and policy exceptions, as informed by fundamental rights standards’ (ACE’s rules explicitly cite the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, the European Convention on Human Rights, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights). Fundamental rights therefore play a role in only a minority of cases, only insofar as they inform the platform’s own rules, and seemingly without overriding effect, should ToS collide with them. In all other cases, the applicable rules are those of the ToS alone.

The idea of applying a contract without any governing law is hardly new. It recalls the private international law theory of the contrat sans loi, and resonates with techno‑libertarian fantasies of self‑sufficient, self‑executing ‘smart’ contracts or anarcho‑capitalist experiments such as special economic zones ruled not by public law but by arbitrable ‘agreements of coexistence’ – ToS under a different label.

Once the ToS are unshackled from any normative framework, little prevents platforms from unilaterally regulating free speech. ODS adjudication risks becoming a rubber‑stamp for moderation decisions falling within the discretion the platforms grant themselves via the ToS, and at most a mistake-correction tool. Applying the ToS in a legal vacuum represents not only an extension of platforms’ de facto power to impose contractual terms on users – it is also quite difficult. Arguably, it is the most challenging of the options considered.

The ToS of most platforms are ambiguous, and ODS bodies may struggle to apply such open‑ended provisions to specific disputes without recourse to outside legal frameworks. In the case of Meta, the need for clearer guidance on how to interpret Facebook’s Community Standards was the mainspring for creating the Oversight Board. Moreover, such standards can range from vague to highly detailed (and idiosyncratic) in prohibiting certain types of content. It is doubtful that an ODS body adhering to a ToS‑only approach could disregard such detailed rules if it judges them inconsistent with the ‘values’ set out in the ToS themselves. From the outset, the Oversight Board asserted the authority to operationalize intra-ToS normative hierarchies (supplementing them with international human rights law at the top), even when this ran against the platform’s own determinations. Yet, while the Oversight Board’s rulings are binding on Meta, an ODS body has no comparable authority to enforce its own interpretation of the platform’s rules. The option of ‘just applying the contract’, then, may prove both cumbersome and ineffective as a check on platforms’ moderation practices.

Finally, the ToS-only strategy may turn Article 21 DSA into a battleground among platform providers. As we explained in previous posts, the Oversight Board Trust, a trust established and funded by Meta, provided substantial startup funding to ACE. Other platforms could follow suit, establishing their ‘own’ ODS bodies through similar financial vehicles. Each such body would then be indirectly linked to a platform provider and yet entitled to seek certification for handling disputes across all Very Large Online Platforms (VLOPs). This is precisely the case of ACE, whose jurisdiction already extends beyond Meta’s platforms to include Pinterest, TikTok and YouTube, and will likely expand further, as it is already certified for all VLOPs. In such a scenario, platform‑backed ODS bodies could exploit the indeterminacy of the various ToS within their remit to promote interpretations they favour, serving as proxies in a battle among VLOPs over the scope of free speech. Like Scottie in Vertigo, ODS bodies that rely solely on ToS may risk becoming entangled in strategies of the very platforms whose power they are meant to check.

Option Two: Uncanny Contract Law

After having witnessed Madeleine’s suicide – or so he believes – Scottie runs into Judy, whom he mistakes for Madeleine’s uncanny double. In a similar way, ODS bodies may feel an unsettling sense of recognition when they set out to identify the law governing the ToS. The jurisprudential setting may look familiar, yet it slips into strangeness when one enters the realm of content moderation.

Since the DSA does not contain specific conflict-of-laws rules relating to ToS, ODS bodies may look to European private international law, in particular the Rome I Regulation, to identify the governing law. That said, ODS bodies are likely not bound to apply Rome I with the same rigor as EU Member State courts. Even arbitral tribunals, after all, have been considered exempt from strict adherence to Rome I when identifying the law applicable to a contract. Still, following the private international law route may be an attractive option for an ODS body, owing to the certainty and predictability it offers.

In many cases, the platform-user relationship is likely to qualify as a consumer contract under Article 6 Rome I. Importantly, the concept of ‘consumer’ in European private international law is broad: the CJEU has held, for instance, that a poker player remained a consumer vis-à-vis an online gambling platform, even after playing nine hours per day and earning as much as 227,000 EUR in one year. Reasoning by analogy, in the context of relationships governed by social media ToS, the notion of ‘consumer’ would encompass not only the average user, but also armies of micro-influencers inclined to file content moderation complaints.

In practice, applying Article 6 Rome I would typically lead ODS bodies to conclude that the governing law is that of the country of the user’s habitual residence. Even if judged fair, a choice‑of‑law clause in the ToS could not deprive consumers of the mandatory protections of the law of their country of residence. By following this approach, ODS bodies would by analogy align their decision-making with the principle of legality reflected in Article 11 of the ADR Directive, thus contributing to the private enforcement of EU consumer law.

That’s where the vertigo kicks in. Consumer law protections, which mainly stem from EU directives and the national contract laws implementing them, have little to do with the issues typically at stake in content moderation disputes. Whereas consumer law traditionally addresses matters such as the sale of goods, product liability, and the provision of certain types of services, moderation disputes largely revolve around freedom of expression and its balancing against other fundamental rights and interests. Applying consumer law in this context requires a re‑situating of its protections, adapting them to a reality – that of social media – where the ‘service’ provided is the enabling of expression. Some Member State courts have gone down this road, invoking the Unfair Contract Terms Directive to test the legality of platforms’ ToS-based speech restrictions. But can ODS bodies, designed to provide fast and inexpensive remedies for disputes unlikely to reach court, realistically do the same?

Another challenge would be navigating the patchwork of multiple national laws, which may push ODS bodies to retrench into national silos. Article 21 DSA, however, points in the opposite direction by enabling the conferral of EU-wide jurisdiction, an option that several certified bodies are already pursuing. The danger is that the complexity of applying contract law to moderation disputes may overwhelm ODS bodies, much like Mr. Ferguson in Hitchcock’s masterpiece: EU consumer law, with its familiar weaker‑party safeguards, becomes eerily elusive as the ground shifts from sales contracts to something as unsettling as ‘speech contracts’.

Option Three: Human Rights Heights

At the climax of Vertigo, Scottie forces himself to climb the bell tower, overcoming his fear of heights to confront Judy about her role as Elster’s accomplice. This painful ascent serves here as a metaphor for the most daring option open to ODS bodies: anchoring their decisions in human rights law. As we will argue, ODS bodies have two ways to exercise this option: testing ToS provisions against human rights law; or embracing the more radical option of applying human rights instead of the ToS.

The DSA itself offers support for a human-rights-based approach, albeit indirectly (i.e., not as instructions given to ODS bodies). Article 14(4) DSA stipulates that platform providers, when enforcing restrictions, shall have ‘due regard to […] the fundamental rights of the recipients of the service, such as the freedom of expression, freedom and pluralism of the media, and other fundamental rights and freedoms as enshrined in the [EU] Charter [of Fundamental Rights]’. As Quintais, Appelman and Fathaigh have suggested, ODS bodies could rely upon this provision to test a platform’s enforcement of its own ToS against human rights law.

What is more, the CJEU has held that certain provisions of the Charter have horizontal effect, and therefore apply directly in relationships between private parties such as platforms and their users. The question has been raised whether the same holds for Article 11 of the Charter on freedom of expression. If that is the case, reliance on Article 14(4) DSA might even be superfluous, since ODS bodies would be under an obligation to treat freedom of expression – and other fundamental rights – as central elements of the applicable law. A different and perhaps more reliable route to the same conclusion lies in Article 1 DSA, which refers to the creation of an ‘online environment […] in which fundamental rights enshrined in the Charter […] are effectively protected’ as an essential objective of the entire Regulation. As a matter of systematic construction, it would be odd to argue that the DSA enabled the creation of ODS bodies licensed to make – and platforms to implement – decisions that conflict with human rights as protected in the EU. In this sense, respect for human rights would constitute the very core of a digital public order shaped by the DSA, from which no component of the system – including ODS bodies – could deviate.

Outside of the European legal order, a human rights turn in the field of content moderation dispute settlement has already happened. The Oversight Board – a body funded by Meta through the Oversight Board Trust – applies the ToS of Meta platforms, including so-called ‘values’. Yet it has consistently made clear that its primary yardstick in reviewing content moderation decisions is international human rights law. Among ODS bodies, User Rights is at present the only one that explicitly relies on a human-rights-based approach – it ‘promotes the implementation of fundamental rights’ – while treating the ToS as a secondary ‘benchmark’.

Anchoring ODS reasoning in fundamental rights seems attractive as it situates disputes in a constitutional framework reflecting shared European values, sidestepping the technicalities of private international law. A bolder variant of this approach, as mentioned above, would be to set aside the ToS and apply only human rights law – sparing ODS bodies the task of navigating complicated, often fast-evolving, and divergent contractual arrangements across platforms. To be sure, this approach would not imply holding platforms to the same human rights obligations as States. An ODS body may find a moderation measure acceptable under human rights law, even though an analogous restriction would be impermissible by a State. In this sense, human rights law would still provide the relevant normative standard, but one tailored to platform governance rather than transposed wholesale from the case law regarding States.

The human-rights-only variant would represent a radicalisation of the Oversight Board’s jurisprudence. The Board has in fact treated international human rights law as hierarchically superior to contractual standards, making it the decisive point of reference in assessing moderation decisions, even in cases where the Board decided that Meta’s human rights obligations differ from those of States. Instead of first applying the ToS and then testing the outcome against human rights law, an ODS body might presume that a moderation decision is in line with the ToS when the decision complies with human rights and set aside the ToS where such compliance is lacking. In the latter case, the message to the platform would be that the ToS clause underpinning the moderation decision must either be modified or construed in accordance with human rights standards. In this way, an ODS body could operate in the manner of a human rights court, focusing exclusively on fundamental rights as the applicable law.

Yet ascending to such jurisprudential heights inevitably invites vertigo. First, it must be recalled that fundamental rights were developed with States in mind, not private corporations. Human rights specialists have long debated whether and how such rights may bind private entities. For ODS bodies, applying fundamental rights consistently may require taking a stance in this complex debate. Since ODS bodies may be called upon to settle, collectively, tens or hundreds of thousands of disputes each year, expecting them to apply human rights law consistently while still delivering swift and inexpensive resolution raises doubts about feasibility. Even arbitral tribunals that take years to settle a single dispute struggle to determine how to apply human rights norms to private corporations.

However, leveraging generative AI might provide ODS bodies with a tool to steady themselves as they reach up towards human rights – much as Mr. Ferguson clung to the bell tower’s ledge. A properly trained large language model, for example, would be capable of producing persuasive arguments in the context of balancing freedom of expression against countervailing rights and interests. Indeed – as one of us will argue in an upcoming conference – the rhetoric of balancing, despite all the prestige it commands, is particularly amenable to imitation precisely because it unfolds by enthymematic (sometimes impressionistic) reasoning rather than by logico-deductive steps. This would not entail relinquishing the task of balancing to the machine but rather regulating the production of AI-assisted decisions.

ODS bodies’ jurisprudential ascent to human rights heights may provide not comfort but clarity – much like Scottie Ferguson overcoming acrophobia. As we noted at the outset, the choice of applicable law in this field cannot rest on sources doctrine alone but requires an experimental mindset and careful balancing acts. A human-rights-based approach – assisted, where appropriate, by AI – may offer a way to keep ODS practice cost‑effective and credible, drawing on the prestige of human rights language, increasing the reputational cost of non-compliance, and fostering the willingness of platforms to cooperate.